Revisiting a bad Beveridge curve take

And offering some hopefully better ones with medium confidence

In early July, on the day JOLTS data for May came out, I was talking to a reporter about the Beveridge curve. Could job openings continue to decline without unemployment rising? I said I thought they could because labor force participation was high, and if labor demand continued to cool, the upward pressure that would exert on the unemployment rate could be offset by declining participation. We also discussed the fact that we seemed to have landed back on the stable portion of the quits-based Beveridge curve as a potential sign that the easy portion of the labor market cool-down had ended and rising unemployment would follow continued declines in openings.

Today, with four more months of data available, the answer to the question “can openings continue to decline without unemployment increasing?” seems so far to have been, basically, yes (the job opening rate fell 0.47 percentage points between May and September while the unemployment rate increased by just under 0.1 percentage points), but my reasoning was completely wrong. Labor force participation has, in fact, increased slightly since May.

Two other job opening-related things have also happened or continued happening since May:

We seem to have dipped a bit below that typically stable quits-based Beveridge curve

The ratio of hires to job openings, sometimes called the vacancy yield, has continued to recover since reaching its lowest level on record in March 2022.

Both declining quits and increasing vacancy yield could help explain how job openings have continued to decline without a meaningful increase in the unemployment rate. If a given number of job openings now produces more hires than it used to, then fewer job openings are needed to complete a given amount of aggregate hiring (if the vacancy yield were still at its January 2022 level, the job opening rate would have needed to be 1.3 percentage points higher than it was in September in order to match that month’s hiring). Fewer quits kick off fewer vacancy chains, as fewer workers to replace require fewer job openings.

Quantitatively, both seem likely to matter, though to varying degrees. Comparing actual openings with what would have been required if the vacancy yield had not continued to recover suggests that vacancy yield recovery could account for 80 percent of the decline in the job opening rate since May. The recent state-level relationship between quits and job openings suggests that declining quits could account for a little over 10 percent of the decline in openings over that period.

More interesting than these exact figures, however, is the question of why these things are happening.

I’m mostly not sure why the vacancy yield is rising

Since March 2022, the vacancy yield has increased by 37 percent and job openings have declined by 39 percent. These are large shifts, especially as they cut against the long-term upward trend in job openings/downward trend in the vacancy yield.

Declining congestion in the labor market is one possible explanation for the rising vacancy yield. When a worker looks for a job or a firm posts a job opening, each imposes a search externality on other labor market participants - each additional opening or application to consider takes time and slows down the matching process. The large reduction in vacancies is itself evidence of reduced participation and potentially reduced congestion on the employer side of the labor market. However, this externality is likely small, so gains from reducing it are also small. One study puts the elasticity of the vacancy yield with respect to vacancies around 0.04, and since the magnitudes of the vacancy decrease and the vacancy yield increase are very similar in percent terms, reductions in employer-side congestion alone likely account for no more than five percent of the increase in the vacancy yield since early 2022.

Unemployed people stand out as job seekers, but the full set of people looking for work is much larger. Many people look for work while already employed, and millions move directly from one job to another each month. More people are hired from out of the labor force every month than are hired from unemployment. Non-participants are a much larger group, so even if their job search activity is limited, intermittent, or opportunistic, they could make a meaningful contribution to overall job search activity.

One direct measure of job search activity shows that the share of people looking for work is at its highest level in just over ten years. Other indirect measures, such as estimates of employer-to-employer transitions from the Philadelphia Fed or the Upjohn Institute, are not entirely consistent but do not suggest a large drop in search among the already employed. The number of marginally attached workers, who are out of the labor force and not actively looking for jobs but are interested in working, is slightly higher than it was in early 2022. And, of course, the number of unemployed workers has been drifting up. None of this suggests that reduced congestion on the worker side of the labor market is contributing to rising vacancy yields.

More speculatively, it’s possible that the vacancy yield has risen as firms maintain more immediately necessary job openings that are more likely to convert into hires while abandoning more speculative, lower likelihood openings as their plans adjust to changes in prevailing economic conditions. This dynamic seems likely to characterize the spikes in the vacancy yield that occur during recessions, and there is some evidence to suggest that it could be a factor now. Since early 2022, small businesses have roughly maintained their actual hiring while seeing fewer good opportunities for expansion and curtailing plans for future hiring.

Even more speculatively, increases in recruiting intensity, relaxation of job experience or training requirements, or improvements in recruiting/hiring processes or technologies could also increase the vacancy yield. Evidence on these channels would be very helpful.

Quits are probably falling mainly because labor demand is falling relative to labor supply

Supply and demand provide a natural place to start trying to understand why quits have fallen below their typically stable version of the Beveridge curve. Since May, labor supply has been unusually high, with prime-age labor force participation reaching levels not seen since early 2001. The current unemployment rate is similar to the rates seen in early 2001, but the quit rate (1.9 percent in September) is lower than the 2.2-2.4 percent seen then. Why is that?

The answer is that labor demand is not as high as a quick glance at job openings might suggest. The current job opening rate (4.5 percent) is a full percentage point higher than it was in March 2001, when the quit rate was 2.3 percent. Job openings, however, have exhibited a clear upward trend over the series’ history. After adjusting for that trend, which the goal of more accurately reflecting underlying labor demand, vacancies in early 2001 were substantially higher than they are now.1 Lower labor demand today alongside similar labor supply makes sense of today’s lower quit rate.

Recent changes in wage growth by job change status are also consistent with this story. During expansions, the Atlanta Fed’s wage growth tracker typically shows faster annual wage growth for workers who change jobs than for workers who remain with the same employer. Those two groups are currently experiencing roughly the same annual wage growth, with growth for job switchers having declined by 0.9 percentage points over the last year to roughly the level of job stayers, which has declined by only 0.1 percentage points over that period. If job switchers’ wages are determined by the relative supply of and demand for labor at the time they switched jobs while job stayers’ wages are determined by the most favorable balance of labor supply and labor demand since their hiring (as suggested by Beaudry and DiNardo, 1991), it would make sense that job switcher wage growth would decline as openings have continued to fall while job stayer wage growth would hold roughly steady.

Improved job match quality is probably only pushing openings down a little bit

The faster labor productivity growth of the last several quarters lurks in the background of this discussion so far. The pandemic induced an enormous amount of churn over a short period, first due to displacement associated with public health conditions and later due to increased quits amid a tight labor market, as well as an almost-as-enormous amount of discussion about the Great Resignation. If the resulting reshuffling of workers resulted in higher quality, more persistent matches with employers, that could be contributing to today’s faster productivity growth and also enabling job openings to continue to decline while unemployment remains low. Better matches would likely lead to fewer quits and layoffs, and consequently, fewer subsequent job openings.

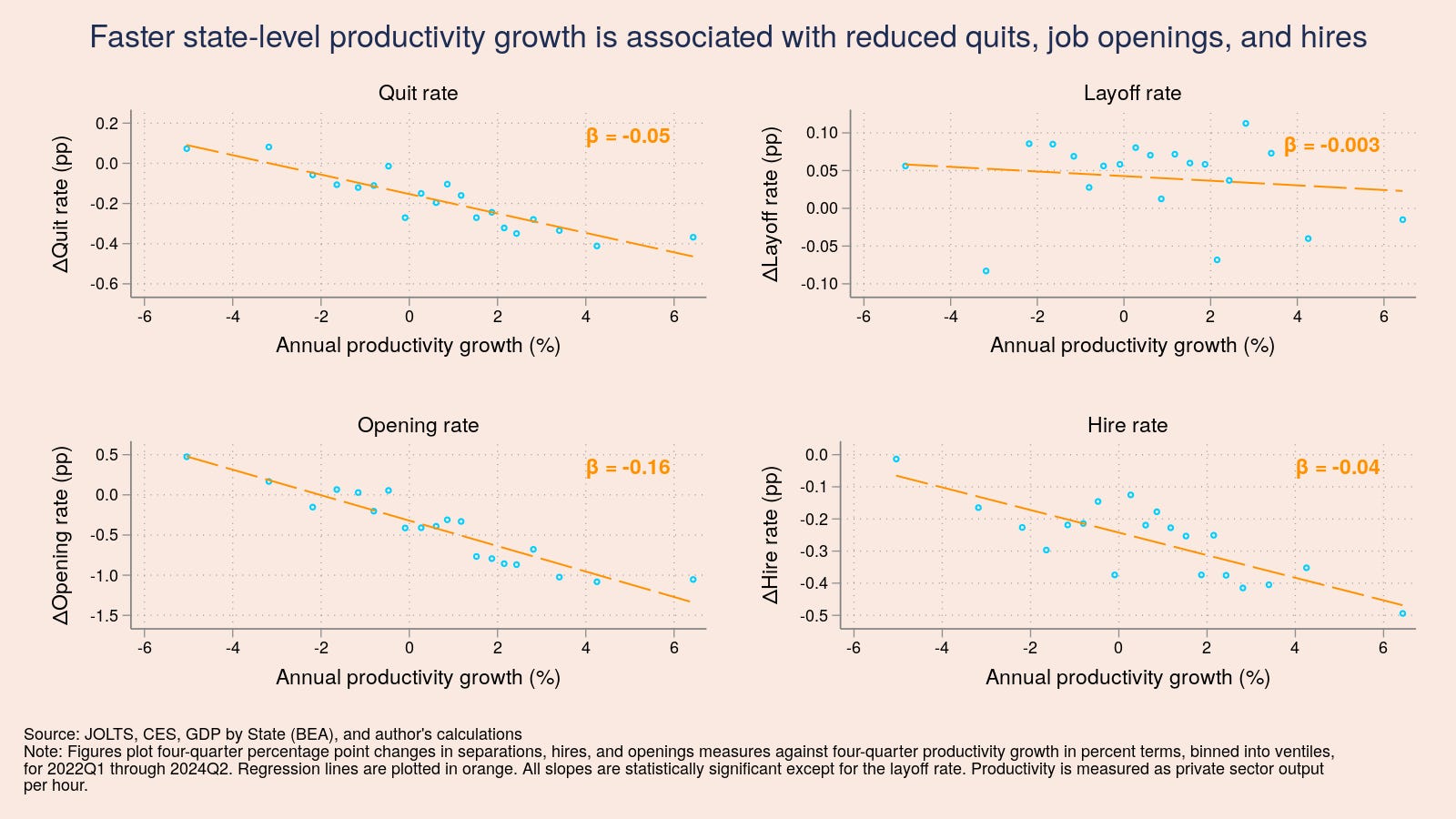

While far from conclusive, this possibility has been borne out in recent data. Nationally, both Quarterly Workforce Indicators and the New Hires Quality Index show new-hire wages increasing after the pandemic and remaining elevated into mid-2023, suggesting scope for improved match quality. State-level data from the beginning of 2022 through the second quarter of 2024 show that places that saw faster productivity (private sector output per hour, technically) growth saw larger declines in quits, openings, and hires.

As for the quantitative importance of this dynamic to the narrower question about the decline in the job opening rate since May, productivity growth in the second and third quarters of 2024 averaged nearly 2.2 percent on an annualized basis. That is nearly a full percentage point higher than average productivity growth from 2010 through 2019. Assuming that the 4 months from May to September accounted for 0.33 percentage points of excess productivity growth, the slope of the regression line in the openings panel in the figure above suggests that the job opening rate would be about 0.05 percentage points lower, about the same as the reduction associated with reduced quits. Because increased productivity is also associated with reduced quits, some of this reduction in openings associated here with higher productivity is likely also associated with reduced quits in the prior analysis, and these estimates should not be added together.

Hiring is probably too low

The main reason that understanding the decline in job openings matters is that it affects hiring, which has also been trending down as the labor force continues to grow, pushing the unemployment rate up. The hire rate is below what one would expect it to be at the current unemployment rate (and EPOP) based on historical data, which suggests it is “too low,” but the real test is whether this rate of hiring is adequate going forward.2

The current hire rate is producing roughly the expected amount of payroll employment growth, in percent terms, and almost exactly the expected amount for an expansionary period. However, that growth is meaningfully slower than the Congressional Budget Office’s June 2024 projection for labor force growth over the next few years. CBO thinks current payroll employment growth would be adequate to keep up with labor force growth in 2028, but between now and then, the labor force will likely grow more quickly. This forward-looking mismatch more conclusively indicates that hiring is too slow.

You can probably trust the quit rate

To offer a potential synthesis of these analyses, falling quits can be a side effect of positive developments like faster productivity growth, and they can have some salutary side effects of their own, like decreased congestion in the labor market, but these considerations seem clearly secondary to the signal falling quits provide that labor demand is declining relative to labor supply. Improved hiring efficiency could let us swap frictional for demand-related unemployment, so it’s possible falling openings could continue to be accompanied by minimal increase in overall unemployment, but only for a while. We should take labor demand signals seriously because, as the too-long recovery from the Great Recession illustrated, abundant labor supply is a terrible thing to waste.

The adjustment used here involves estimating a linear trend in the job opening rate using pre-pandemic data, calculating residuals, and adding residuals to the average opening rate over all months with data. The figure below presents the adjusted series alongside the unadjusted series. Alternative approaches may produce somewhat different numbers in a given month but should generally elevate openings earlier in earlier months in the series relative to later months.